Wushan Ningzhen Temple: A Fusion of Faith Amidst a Thousand Years of Incense

Deep within the clouds and rain of Wushan, an ancient temple with green bricks and gray tiles stands quietly on a steep cliff in the east of the city. The eaves and corners pierce through the clouds and mist, and the vermilion-lacquered gates bear the marks of time. This is the Ningzhen Temple, which has carried the faith of the ancient Ba and Chu peoples for a thousand years. The morning bells and evening drums transcend time and space, weaving the legend of Yaojie’s flood control and the teachings of the Three Pure Ones into the longest cultural tapestry along both sides of the Wu Gorge.

Trace its origins, and the original name of the Ningzhen Temple is closely linked to the legend of a divine maiden. In ancient times, the floods of the Wu Mountains were overwhelming, and Yu the Great’s efforts to control the waters were hindered.

Yaoji, the daughter of the Western Queen Mother, moved by the suffering of the people, descended from heaven, using clouds as maps and mountains as markers, to guide Yu the Great in clearing the path through the Three Gorges. When the perilous rapids of the Wu Gorge were transformed into a navigable passage, the people could finally live in peace and prosperity. Later generations built a temple at the site where Yao Ji manifested her divine presence, venerating her as the “Goddess” and enshrining her as the “Goddess Temple.” The original statue inside the temple is said to depict Yao Ji wearing a cloud-like robe and holding the map for flood control, her brows exuding both the ethereal grace of a divine being and the tender compassion for all beings.

After the Ming Dynasty, this ancient temple underwent a significant transformation. With the rise of Daoism in the Ba-Shu region, the Goddess Temple was renamed “Ningzhen Guan,” meaning “to condense true energy and attain enlightenment.” The layout of the temple was adjusted accordingly, retaining the Yaojī Hall while adding the Three Pure Ones Hall, where the highest deities of Daoism—the Primordial Lord, the Lord of the Divine Treasure, and the Lord of Virtue—were enshrined. This overlap of beliefs was not a simple replacement but formed a remarkable symbiosis: on the left, the Three Pure Ones Hall was filled with incense smoke as Daoist disciples recited the Daodejing; while on the right side, the Yaoji Hall flickers with candlelight as boatmen sincerely pray for safe passage through the gorge. The two faiths coexist harmoniously under the same roof, much like the mist and waters of Wushan Mountain, blending into a unique cultural landscape.

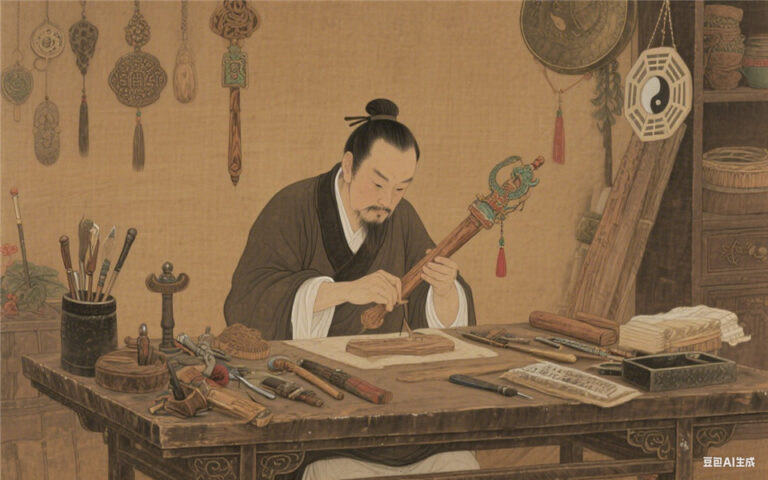

As one strolls through the temple, the most striking feature is the Ming Dynasty-era statue of Yaoji. The statue has shed its earlier mythical elements, gaining a more ethereal Taoist aura. The map of water control in her hand has been transformed into a whisk, yet she still retains the posture of pointing to the river. The murals inside the Sanqing Hall hold a hidden meaning. The painter skillfully integrated the scene of Yaojī controlling the water into the Taoist “Heaven, Earth, and Humanity” triad diagram, achieving a visual resonance between mythical legends and Taoist philosophy. This wisdom of cultural fusion is also reflected in the inscriptions on the steles within the temple. The phrase “The divine maiden reveals her true form; the Three Purities bear witness to the Dao” from the Ming Dynasty stele reveals the spiritual core of this ancient temple that spans thousands of years.

Today, the temple remains bustling with incense and worshippers. Among the pilgrims are both modern travelers seeking blessings and devoted Daoist practitioners. As the winds of the Wu Gorge sweep through the ancient cypress trees before the temple, rustling the bronze bells on the eaves, one can almost hear the ancient people’s praises of Yaojī intertwined with the chanting of the Daoist priests. This ancient temple, which has weathered the vicissitudes of time, has long transcended its role as a mere religious site, becoming a living fossil of the evolution of faith in the Three Gorges region—it bears witness to how myths and legends have crystallized into cultural memory, and records how local beliefs and Daoist culture have achieved a perfect reconciliation and symbiosis over the centuries.