Mengcheng Zhuangzi Shrine: A spiritual home with a thousand years of Taoist charm

In the eastern part of Mengcheng County, Anhui Province, by the banks of the Wu River, the Zhuangzi Temple stands like a silent sage, watching over the passage of a thousand years. This temple, which embodies the essence of Daoist philosophy, has witnessed the rise and fall of dynasties, serving as a condensed cultural history.

In the first year of the Yuanfeng era of the Song Dynasty (1078), County Magistrate Wang Jing founded the Zhuangzi Temple on the north bank of the Wu River in Qiyuan City. This land has a deep connection with Zhuangzi, as it is said to be where he once served as an official in the Qiyuan region, and the spirit of the “proud official of Qiyuan” took root here. Unfortunately, the Yellow River’s floods were relentless, and the newly built temple was eventually swallowed by the muddy waves, leaving only a sense of sorrow after the waters receded.

In the ninth year of the Wanli reign of the Ming Dynasty (1581), County Magistrate Wu Yiluan rebuilt the temple at its current site, giving Zhuangzi’s philosophical thoughts a new home. By this time, the Zhuangzi Shrine had already taken on a grand and majestic appearance: within the Xiao Yao Hall, one could almost hear the recitation of “The Free and Unfettered Wanderer,” and within the Meng Die Tower, one could almost see Zhuang Zhou’s transformation into a butterfly.

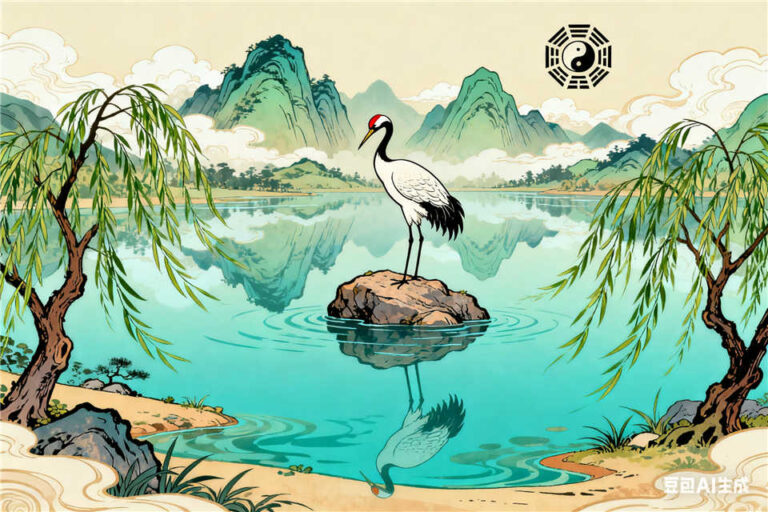

The Yu Chi Bridge spans the emerald waters, and the Guan Yu Terrace stands by the water’s edge. Among the Daoist dwellings, one could almost sense Daoists engaged in earnest cultivation. The meticulous layout subtly aligns with the Daoist concept of “unity between heaven and humanity,” blending architecture and nature seamlessly.

In the fifth year of the Chongzhen era (1632), Magistrate Li Shifang renovated the Xiao Yao Hall, added the Wuhua Pavilion, and transformed the pond into the “Hao Shang Guan Yu Garden.” The wisdom of the “Huo Liang Debate” is reenacted here—the graceful fish swimming in the water mirror the Daoist pursuit of natural authenticity. Among the pavilions and terraces, visitors can contemplate Zhuangzi and Huizi’s philosophical dialogue on “knowing the joy of fish,” letting their thoughts roam freely amidst the water, light, and tree shadows.

However, the ravages of time and war eventually led to the gradual decline of this temple steeped in Daoist charm. Though the remaining ruins no longer match the scale of its former glory, they still convey the spiritual power that has endured for millennia. Among the crumbling walls and ruins, one can almost see Zhuangzi dragging his tail through the mud; amidst the lush grass, one can faintly hear the Daoist maxim of “governance through non-action.”

The rise and fall of the Zhuangzi Shrine in Mengcheng is not merely the tale of a temple’s vicissitudes; it is a testament to the enduring presence of Daoist culture in the world. Like a mirror, it reflects the Chinese people’s eternal pursuit of spiritual freedom, allowing Zhuangzi’s wisdom to shine through the dust of history, still radiant along the banks of the Wu River.