Songjiang Yuehe Taoist Temple: Shanghai’s Taoist Legacy Lost to Time

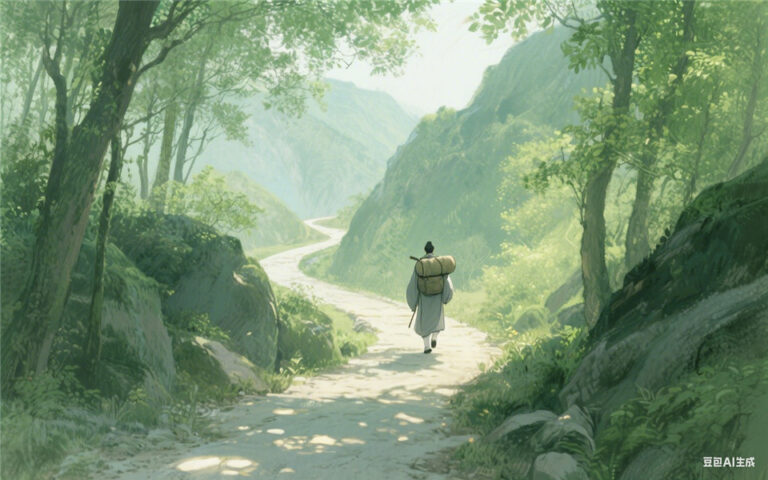

In the historical annals of Songjiang, Shanghai, once stood a Taoist sanctuary—Yuehe Taoist Temple—that embodied both Taoist culture and local memory. Though now buried beneath the dust of time, the scattered historical records that remain sketch a vivid portrait of Qing Dynasty Taoist sites in Shanghai. This Taoist temple served not only as a venue for religious activities but also bore witness to the social transformations of the Songjiang region from antiquity to modernity, becoming an indispensable link in the local cultural fabric.

1.Geographical Location: A Water-bound Taoist Realm West of Qianjiaqiao

Yuehe Taoist Temple was situated west of Qianjiaqiao in what was then Songjiang County, Shanghai. This location embodies the quintessential characteristics of a Jiangnan water town. During the Qing Dynasty, Songjiang Prefecture was crisscrossed by waterways. Qianjiaqiao served as a vital transportation hub connecting surrounding villages and towns. The Taoist temple’s location here facilitated easy access for devotees while aligning with the Taoist principle of “following nature’s way.” Built alongside water, the layout satisfied the cultural need for proximity to water in Taoist rituals and allowed the temple to blend seamlessly with the water network ecosystem of Jiangnan.

Historical maps indicate that the area west of Qianjia Bridge belonged to the core region of Songjiang Prefecture during the Qing Dynasty, surrounded by farmland, residences, and shops. The presence of the Taoist temple added a touch of serene tranquility to this secular landscape. Scattered records in the Songjiang Prefecture Annals describe the surroundings as once graced by weeping willows along the banks and the evening songs of fishing boats. Devotees seeking blessings had to travel along the waterway, crossing stone bridges to reach the temple. This “gazing upon the Tao across the water” evoked a profound sense of sacredness and transcendence.

2.Historical Evolution: The Renaming Journey from Zhou Gong Hall to Yuehe Taoist Temple

Yuehe Taoist Temple did not emerge from nothing. Its predecessor, “Zhou Gong Hall,” owed its name to local sacrificial traditions. “Zhou Gong” most likely referred to either a local sage honored for his merits or a Taoist deity. The hall initially served as a folk sacrificial site before gradually evolving into a space for Taoist activities. This transition from a folk shrine to an official Daoist temple reflects the deep integration of Daoism and folk beliefs in the Songjiang region during the Qing Dynasty.

In the 47th year of the Qianlong reign (1782), Zhou Gong Hall was formally renamed “Yuehe Daoist Temple,” a change of great historical significance. The name “Yuehe” (Moon River) likely derives from the river’s meandering form surrounding the temple. — on full moon nights, moonlight reflecting upon the water aligned with Taoist doctrines of “moon worship” and “harmonizing yin and yang.” The designation “Daoist temple” signified its elevation from a folk shrine to an officially recognized Taoist institution, bringing greater standardization to its regulations and functions. Historical records suggest that after the renaming, Yuehe Daoyuan likely added structures such as the Hall of the Three Purities and the Wenchang Pavilion, becoming one of the major centers for Taoist activities in the Songjiang region.

3.Architectural Style and Cultural Function: The Earthy Charm of a Water Town Taoist Site

Although no physical remains of Yuehe Taoist Temple survive today, we can reconstruct its general appearance by combining the common characteristics of Qing Dynasty Taoist architecture in the Jiangnan region with local historical records. The temple most likely employed the traditional Jiangnan brick-and-wood construction method, arranged along a central axis. The front featured a mountain gate, the center housed the main hall, and the rear contained monks’ quarters, with side halls and ancillary rooms flanking both sides. The mountain gate likely bore a plaque inscribed with “Yuehe Taoist Temple.” The main hall enshrined the Three Pure Ones or the Supreme Emperor of the North, while the side halls were dedicated to deities closely tied to folk life, such as the God of Literature and the God of Wealth, reflecting Taoism’s integration into daily existence.

Culturally, Yuehe Taoist Temple served not only as a place for devotees to pray for blessings and perform ritual feasts, but also fulfilled roles in local education and public welfare. During the Qing Dynasty, when floods frequently struck the Songjiang region, the temple often held rain-invoking and disaster-warding ceremonies to pray for the people’s safety. simultaneously, the temple may have established free schools to teach nearby children literacy, or distributed relief porridge during famine years, serving as a bridge between religion and secular society.

4.Ruins and Remnants: Cultural Echoes Through Time

Historical records offer no definitive date for the Moon River Taoist Temple’s abandonment, though it is speculated to have occurred during the late Qing or early Republican eras. Amidst the influx of Western culture, social upheaval, and shifting religious policies, many traditional Daoist sites gradually declined, and Yuehe Daoist Temple was no exception. It likely fell into disuse after losing its devotees, then was demolished during wartime or urban development, ultimately vanishing from the earth. Only its name and scattered records remain in local historical annals.

Though we can no longer witness the original form of Yuehe Daoist Temple, its historical value endures. First, as tangible evidence of Qing Dynasty Daoist development in Songjiang, it provides crucial clues for studying the evolution of Daoist culture in the Shanghai region. Second, the monastery’s rise and fall is inextricably linked to the geographical and social transformations of the Qianjiaqiao West area, making it an integral part of Songjiang’s local history. Third, the principles it embodied—“following nature’s way” and “benefiting the world and its people”—still hold profound significance for contemporary society.